The UML is a general-purpose, tool-supported, and standardized modeling language that is used in order to specify, visualize, construct and document all the elements of a wide range of system intensive processes. It promotes a use case driven, architecture-centric, iterative and incremental process, which is object-oriented and component-based. The UML is broadly applicable to different types of systems, domains, methods and processes, which is why it is such a popular and broadly used language.

However, even though the UML is very well-defined, there might be situations in which you might find yourself wanting to bend or extend the language in some controlled way to tailor it to your specific problem domain in order to simplify the communication of your objective. This is where the UML extension mechanisms come in.

The UML provides a standard language for writing software blueprints, but it is not possible for one closed language to ever be sufficient to express all possible nuances of all models across all domains across all time. For this reason, the UML is opened-ended, making it possible for you to extend the language in controlled ways.

UML defines three extensibility mechanisms to allow modelers to add extensions without having to modify the underlying modeling language. These three mechanisms are:

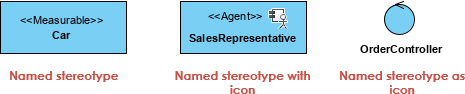

A stereotype extends the vocabulary of the UML, allowing you to create new kinds of building

blocks that are derived from existing ones but that are specific to your problem. They are used for classifying or marking the UML building blocks in order to introduce new building blocks that speak the language of your domain and that look like primitive, or basic, model elements.

For example, if you are working in a programming language, such as Java or C++, you will often want to model exceptions. In these languages, exceptions are just classes, although they are treated in very special ways. Typically, you only want to allow them to be thrown and caught, nothing else. You can make exceptions first-class citizens in your models, meaning that they are treated like basic building blocks, by marking them with an appropriate stereotype, as for the class Overflow as shown in the Figure below:

Model New types in UML

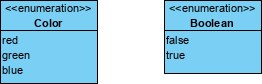

Another Example, an enumeration types, such as Coloroolean and Status, can be modeled as enumerations, with their individual values provided as attributes:

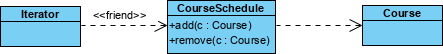

Model Special Relationship

A dependency can have a name, although names are rarely needed unless you want to use stereotypes to distinguish different flavors of dependencies. For example:

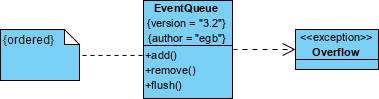

A tagged value extends the properties of a UML building block, allowing you to create new information in that element’s specification. They are properties for specifying keyword-value pairs of model elements, where the keywords are attributes. They allow you to extend the properties of a UML building block so that you create new information in the specification of that element. Tagged Values can be defined for existing model elements, or for individual stereotypes so that everything with that stereotype has that tagged value. It is important to mention that a tagged value is not equal to a class attribute. Instead, you can regard a tagged value as being metadata, since its value applies to the element itself and not to its instances.

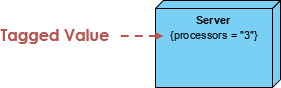

Graphically, a tagged value is rendered as a string enclosed by brackets, which is placed below the name of another model element. The string consists of a name (the tag), a separator (the symbol =), and a value (of the tag) as shown in the Figure below:

You can specify just the value if its meaning is unambiguous, such as when the value is the name of the enumeration.

One of the most common uses of a tagged value is to specify properties that are relevant to code generation or configuration management. So, for example, you can make use of a tagged value in order to specify the programming language to which you map a particular class, or you can use it to denote the author and the version of a component.

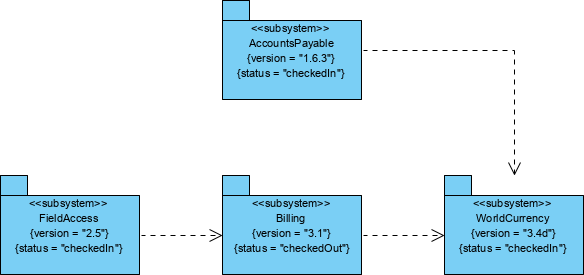

Suppose you want to tie the models you create to your project’s configuration management system. Among other things, this means keeping track of the version number, current check-in/check out status, and perhaps even the creation and modification dates of each subsystem. Because this is process-specific information, it is not a basic part of the UML, although you can add this information as tagged values. Furthermore, this information is not just a class attribute either. A subsystem’s version number is part of its metadata, not part of the model.

The Figure below shows four subsystems, each of which has been extended to include its version number and status. In the case of the Billing subsystem, one other tagged value is shown – the person who has currently checked out the subsystem.

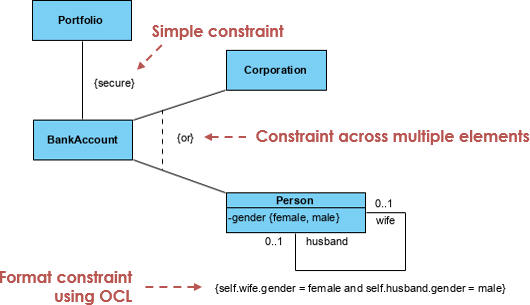

A constraint is an extension of the semantics of a UML element, allowing you to add new rules or to modify existing ones. They allow you to extend the semantics of a UML building block by adding new rules or modifying existing ones. A constraint specifies conditions that must be held true for the model to be well-formed. This notation can also be used to adorn a model element’s basic notation, in order to visualize parts of an element’s specification that have no graphical cue. For example, you can use constraint notation to provide some properties of associations, such as order and changeability

Graphically, a constraint is rendered as a string enclosed by brackets and placed near the associated element or connected to that element or elements by dependency relationships. The example below shows, you might want to specify that, across a given association, communication is encrypted. Similarly, you might want to specify that among a set of associations, only one is manifest at a time.

UML provides several extension mechanisms that allow you to do this without having to modify the underlying modeling language. These mechanisms let you add new building blocks, modify the properties of existing ones and even change their semantics.

The UML extension mechanisms provide not only a means for communication but also a framework for the knowledge and experiences of the individuals within a development culture such that the culture can evolve. They might not meet every need that arises within the development of a project, but they do accommodate a large portion of the tailoring and customizing needed by most modelers in a simple manner that is easy to implement. When you extend a model with stereotypes, tagged values, or constraints,

It is imperative to keep in mind that an extension deviates substantially from the standard form of the UML and that by using it you might, therefore, encounter some interoperability problems. For this reason, it is essential to carefully weigh benefits and costs before using the extension mechanisms and only do so when absolutely necessary.

While UML extension mechanisms like Stereotypes and Constraints offer flexibility, applying them accurately across large projects can be complex. Visual Paradigm’s AI ecosystem helps you define, apply, and manage custom domain extensions with precision.

While UML extension mechanisms like Stereotypes and Constraints offer flexibility, applying them accurately across large projects can be complex. Visual Paradigm’s AI ecosystem helps you define, apply, and manage custom domain extensions with precision.

Describe your domain-specific needs and let the AI suggest the most appropriate stereotypes and tagged values to extend your model.

Follow a guided AI workflow to evolve your diagrams, ensuring that custom constraints and rules are consistently applied as your model grows.

Automatically generate extended UML diagrams that incorporate project-specific metadata and architectural rules instantly.

Document your custom modeling standards and manage AI-generated extended diagrams in a single source of truth.